by Suzy Subways

March 23, 2015 marks 20 years since the CUNY Coalition Against the Cuts’ legendary “Shut the City Down” protest in 1995, which saw an estimated 25,000 young people pack City Hall Park and get attacked by Giuliani’s police force while attempting to march on Wall Street. Sixty people were arrested. In these interviews conducted by Amaka Okechukwu and myself, organizers talk about that day, how they made it happen, what they were up against, what they might have done differently, and what it meant to them. As a participant as well as an interviewer, I’ve decided to step back and share the perspectives of other participants, using their first names, because—well, we go back a long time.

“These Protests…Suddenly Erupted”

The proposed budget cuts to the City University of New York in 1995 were severe—and an insult to a movement with a history of winning massive, radical gains such as CUNY’s open admissions policy and a bilingual community college in the 60s and 70s, when tuition was still free. In addition to a $1,000 tuition increase, Governor Pataki announced plans to cut the Tuition Assistance Program and eliminate SEEK and College Discovery, academic support programs that enabled Black and Latino New Yorkers who’d been under-served by their neighborhood schools to have a chance at college.

Students at CUNY’s 17-plus colleges got angry—and started organizing. Lenina Nadal* describes an early meeting at Hunter College: “There were like 150 people…. A lot of people were very emotional. This was mostly people from immigrant families, first in their family to go to college, and the idea of not finishing was just so horrible.” Heidi, a Brooklyn College student activist at the time, says students there also feared they would have to drop out. “Somehow, these protests that happen every year that are usually kind of small suddenly erupted into something much, much bigger,” she remembers. “People were throwing the word neoliberalism around, and people were talking about austerity.”

Orlando Green was an organizer with the People of Color Club at Baruch College and made the space a hub of activity while interacting with students wherever they congregated. “Prior to meeting up with the CUNY Coalition…we said, “We’re going to talk about budget cuts with whatever we’re doing. Spades tournament—budget cuts. Party—budget cuts. Whatever people are doing for fun, we’re going to do that plus budget cuts.” Orlando’s group also organized Black History Month events that started conversations on access to education and Black radical thought. “And everyone’s coming into our office who wants to put up fliers or get information.”

Sandra Barros also remembers creatively approaching the urgency of organizing. “In the hallways of Hunter College, we would take an opportunity, if there was a group of students, and stand on a table and kind of make an impromptu speech,” she says. “The way we had to do it was a way that very literally broke through these divisions…that society sets up, that says, ‘Here’s this issue, it’s affecting all of you, but no one’s going to talk about it. Nobody’s going to address it, and we’re going to continue on with business as usual.’”

Campus groups from around the five boroughs met up as the CUNY Coalition to plan a citywide response. The coalition’s meetings soon grew to several hundred people and would take all afternoon. Rob Hollander, then a student at the CUNY Graduate Center, compares these meetings to the general assemblies of Occupy Wall Street. “When you look at Occupy and the number of people from CUNY who were at Occupy and the role they played, I think there were a lot of roots of Occupy in the CUNY Coalition, in this, what they now call ‘horizontal organizing.’… The big players made a difference in virtue of what they said. Not in virtue of doing something behind the scenes or having a special role. But simply in virtue of what they believed and their articulateness in conveying what they thought was ideal.”

“Shut the City Down!”

The CUNY Coalition drew a host of radicals from different theoretical backgrounds. Ramiro Campos,* a Hunter College student at the time, says, “They would tie ethnic studies to a larger global movement…. I think the anarchists had the most impact, in the sense that they had less people but they were very influenced by the Zapatistas, and they were able to leverage those ideas of organizing. It became pretty explicitly anti-neoliberal as a main—we didn’t necessarily call it that, but their main focus. And the slogan was, ‘The cuts are not a force of nature.’ That this was very man-made…. And that people needed to organize.”

Christopher and the Hunter contingent as a whole argued against applying for a permit. Sandra explains, “If we got a permit, we were doing things within the control of—the administration in New York City wanted to keep everything under control. And having a token expression, but not have any real power. If we didn’t get a permit and took action outside of what we were mandated to do by the police or by the mayor’s office, we stood the greatest chance of inspiring people that a change could happen.”

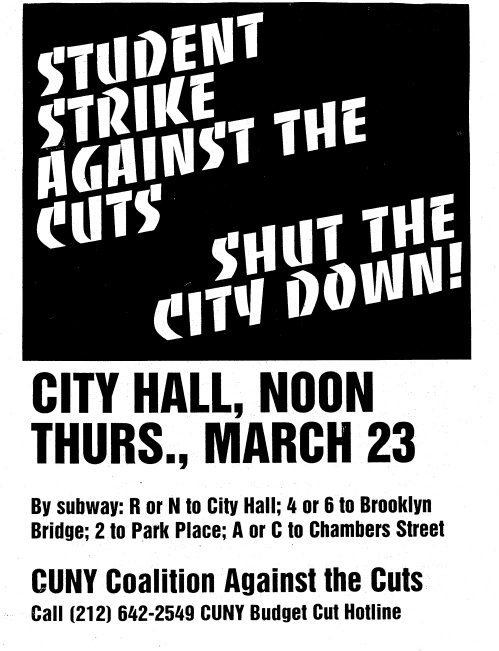

“At a certain point, we decide that the slogan is, ‘Shut the City Down! March on Wall Street!’ and we make this decision not to get a permit,” Christopher says. “I remember making a flier—very simple, but with the slogan very prominently featured.”

“It was clear that this was a key moment in the city,” Sandra says. “That this was an event that could shift things in a real way in the bigger picture. So it was really important for us to say, ‘We’re going to try to push and shut the city down—if we can make it happen.’ And so, I feel like we always brought that. And I think that…was rooted in the real belief that change was possible, and that people have the power. People organized have the power to make [change] happen.”

Sandra adds that decisions about applying for a permit or not are made best when considering the goals and dynamics at play—not from a place of dogmatic or rigid thinking. “I would be of the ones who would fall into, ‘We need to do this either without a permit, or if we can’t, then take a breakout march after that,'” she says. “As respectfully as possible to the other constituents that are there.”

With the appearance of the flier, outreach began in earnest around the city. Rob allowed the coalition access to a photocopier at the Graduate Center. “And that photocopier fueled the demonstration!” he says, laughing. “In particular, through the effort of [City College organizer] David Suker, who would come by and take huge boxes—I mean, it was almost like a comic character. This one guy, with these huge boxes on his shoulder carrying out thousands and thousands of fliers…. And he was handing them out everywhere. He was handing them out to high school students.”

And the high school students were organizing too. “At the time, I was working as a nanny for this little boy, and I dropped him off at his daycare,” Christopher says. “And I was getting back on the train, and there were students from…. Near Lincoln Center, there are two high schools that have very different demographic profiles that are right across the street from each other. But they were leafleting students who were showing up for class…and it’s the flier that I designed, with the bottom reworked for a high school students’ contingent!”

What happened in Albany on February 27th would convince many that the students were ready to shut the city down. During a lobby day organized by the liberal New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), hundreds of CUNY and SUNY (State University of New York) students stormed the state capitol. Christopher remembers, “NYPIRG is basically setting up their marshals to channel us back into the area in front of the state capitol, where we can continue to rally, and instead, a bunch of us head right into the capitol building. And the marshals try to stop us, the police try to stop us, but it doesn’t work, and we’re a large enough crowd, and we bust into the thing, and I just remember people chanting…’Revolution! Revolution!’”

Jed Brandt handcuffed to a hospital bed with visible bruises after being attacked by police outside Hunter College. Photo by Ersellia Ferron.

Next, at Hunter, a mock funeral procession took the streets of the posh Upper East Side—and police responded violently. Sandra Barros recalls, “Jed Brandt was attacked. And there’s a famous picture of him sort of face down on the floor with his arms tied behind his back with the police on top of him. And that was really galvanizing. People—students, faculty—were really, really angry. Like, ‘This is our university. This is our campus. We were right in front of the campus. How dare you come and attack students?’ And so it galvanized us because of the way the police came down on us, but also galvanized us in saying, ‘We have power. And we’re willing to exercise that.’”

In the final lead-up to the protest, Christopher says, the faculty union and the powerful District 1199 health care workers’ union, led by Dennis Rivera, balked at endorsing the coalition’s plans. “But we’ve got a large group of students who are really amped about the kind of demonstration this is conceived of as being,” he says. “And there’s a bunch of—Governor Pataki makes some public appearances in different places, and people are shouting him down. So there’s a sort of rising tide of popular discontent around this budget. And we’re feeding it big time, and it’s increasingly confrontational. And then March 23rd happens, and it’s huge. We bring several thousand people from Hunter College down on the trains. I think the best estimates were 25,000 people, upwards of 40,000, but I think it was 25,000. Probably half of them are high school students.”

“We Filled Two Trains”

CUNY schools turned up in force too. “What was significant at City College is that we used a lot of arts materials and placards,” David Suker* says. “For days before—and there’s this guy Carlos Torres who’s in Yerba Buena, he’s a Puerto Rican activist and musician now, and he was very instrumental in helping to paint banners. So City College, we had multiple banners, multiple flags with ‘CCNY’ on them, all sorts of handmade placards…. Up until the day, that week, we were painting stuff in the rotunda, so everybody at City knew there was a huge demonstration coming up…. The day of, we had a major rally, and we marched…and took Amsterdam down to the A train. And everybody got on the train. It took two trains to hold everybody, just from City College…we packed two trains.”

Photo by Ersellia Ferron, as it appeared in the Spheric newspaper, Vol. X, #1

Brooklyn College also packed the subway. “On that day, I think everybody came together, and we did what we usually do when we have to organize for a protest in Manhattan—you gather people in the Quad, and you just spend the whole day making a lot of noise and giving out fliers,” Heidi says. “And then, eventually, we had built up such a large group of people…we didn’t pay the fare, and we just rolled everybody into the subway. And then filled, I think maybe two trains, and then went down to City Hall…. After a while, the police started to close the subway stations to try to control the people flowing into the march.”

Sandra Barros didn’t arrive with other Hunter organizers on March 23rd—she marched across the Brooklyn Bridge to City Hall with family members and students from one of her favorite classes, whom she had encouraged to attend. “I was in this class—I was in Latina Life Stories—and myself and the professor organized the other students to go. And I organized my family to go—my sister and her girlfriend.” She remembers the protest as reflecting that deep and wide mass base: “It was incredible, walking across the Brooklyn Bridge with so many people. That’s when I realized there were elementary school kids, middle school kids, coming with their teachers. There were members of the different unions who were out there that day. And it really had the sense that we were making an impact. That this was not going to go by unnoticed. That we, again, that we had this power. This was the people’s moment to say, ‘We’re not going to allow this to happen.’

“And when we got there,” Sandra continues, “being in a sea of beautiful faces and amazing people from all walks of life, all over New York City, it felt like a celebration.”

“The March 23rd, 1995 rally was incredibly successful,” Ramiro Campos says. “I think the newspapers said 10,000, but a lot of the organizers said it was 20,000 to 30,000, because so many people could not get into the park. And it was incredible, because there were three American flags at the park, and they were taken down, and the Puerto Rican flag went up, the Black liberation flag went up, and then the black anarchist flag went up. And there was just incredible roaring and cheering in the crowd.”

“It Was Huge…It Was Electrifying…It Was a Fiasco”

But even with tens of thousands of young people, the CUNY Coalition’s tactical team hit a wall when it came time to march—a wall of cops. “I was part of the security team just for bringing Baruch’s group there, and then being a marshal overall—I wasn’t tactical,” Orlando Green says. “I don’t know if I would have done anything different with what we knew back then…. In hindsight, I wish we’d just had more people with those experiences…. We’d met people who’d done campus takeovers, but never had a mass demonstration with no permit trying to leave the march area, have your audio shut down by the police, where leadership can’t even communicate to the marshals or the crowd…. ‘We’re going to march on Wall Street now! We’re going to take the streets!’ And then, at that point, it was like, ‘Click!’ Whoever was talking on the stage, you just saw their lips moving, and everybody in the crowd is like, ‘What’s going on?’”

“And it was huge, and it was electrifying and exciting, and there were speeches, and it was a fiasco,” Christopher says. The CUNY Coalition’s decision to refuse a place behind the mic to politicians continued to be debated on the stage itself. “There was a whole layer of people who were really pissed about that,” he says. “I wasn’t listening to the speeches, I was moving through the crowd…. We were in City Hall Park…. It was surrounded by police barricades, and it was full. It was packed. And so there are thousands of people in the streets off to the side of City Hall Park, and Broadway is basically controlled by the police, and they’re letting traffic through and so on…. There was a massive police presence that is determined not to let us march on Wall Street…. Because if we marched on Wall Street, who knows what we would have done on Wall Street? But the crowd is pushing against the police, in part because it’s just overcrowded…. People are shouting, ‘March! March!'”

Sandra Barros and her companions tried to take the street when they heard the announcement from the stage, but the police were dead set against it—and against anyone taking photographs. “That was the first day I saw Ydanis Rodriguez in action,” she says. “He was one of the organizers that I later met, and he had a bullhorn in his hand and he was calling people to come to the street. And I was with my sister. And it was just very clear for us that that’s what we needed to do. She kind of—I think she had a camera, I don’t recall what it was, but she almost got in a physical altercation with a cop.”

But not all the tactical team members elected by the coalition had their minds set on making it to Wall Street. “While there had been a commitment to…marching on Wall Street, at the actual moment, there’s a failure of nerve,” Christopher says. “Nobody can see a way to break through the police. But in part, it’s because they’re not trying, and they don’t think that way. That’s not how they think about what to do at a demonstration. So the people there with experience breaking through police lines is—there’s a much smaller subset…. You need to focus your forces on a single point, and you need to break that point, and you need to break into the street. And in order to do that, you need some determined people who are willing to get arrested and get their heads cracked.”

“There were people everywhere—the place was packed,” David says, adding that since Giuliani renovated City Hall Park, fences and bushes would make this massive a popular presence there impossible now. “But I remember people talking, and going on and on and on, and at some point, I went up to the stage and said, ‘People are leaving—we’re not going to have a march! And I don’t remember who I spoke to exactly, but I think it was Jed. I said, ‘Look, we need to get out. We need to start marching, because there’s going to be nobody left.’ And he said, ‘OK, take your people, and we’re going to announce a march.’ So we had the banners from City College. I said, ‘I’m going to take the banners, and we’re going to start marching toward the exit—this way,'”—toward a small area between the police barricades. “The only way we could have gotten out of City Hall was going north to try to access Broadway. So we went north along—between the barricades and City Hall Park, and we took a bunch of students along with us…. the toughest kids at City College, which were the Dominican Club, and they were a bunch of big Dominicans, so we had them up front. And eventually, we came up against the cops.”

“We eventually get up to right where the park ends…Chambers Street. And they’d set up a line of cops. And we got up there, and we just said, ‘Alright! One, two, three!’ And we massed, and people were pushing forward. Sarah was right next to me, from [College of] Staten Island. There was a good five minutes where people were pushing…. This was like ten deep or more, where people were just pushing forward. And at some point, the cops had let them through. So they let the first lines through, and then they just beat everybody up. So that’s what—they beat us and arrested us. The first line. But then the Dominican guys who were there, I asked them the next day, “What happened to you guys?” and they said, “We fought with the cops and we got out of there!’ So there was a portion of people who got arrested, like me and Sarah got arrested, on the front lines. But they fought with the cops and must have just gotten out…. The first line had a scuffle with the cops, and there was a second line, and that’s when the cops knew they weren’t going to have enough people to hold back this mass. And I don’t know how deep the mass was, or how militant the mass was, but they let them through, and that’s when the march around City Hall was.” The remainder of the crowd in City Hall Park did not make it in time to this brief space that opened up in order to follow that mass of protesters out and onto Broadway.

“At that point, people were just trying to get out,” Orlando says. “People were just doing stuff on their own. I remember being, at some point, in with the crowd, trying to push through a barricade with police on the other side. And I was—it was me and Rory—had the crowd behind us, and a line of cops right in front of us, and we were pushing the cops. But we were telling the cops, ‘It’s not us. It’s the crowd behind us,’ just to throw them off. ‘Like, please don’t beat me. It’s just the crowd behind me. I can’t turn back.’ I don’t even think that got us out. That just got us to a certain point.”

“I think at the Northwest corner, there was some scuffling, fighting, and maybe rioting,” Rob says. There were a whole bunch of arrests. I either hadn’t gotten there or I had already gone past that area. I was back in the South end of the park again…. Everybody was very alarmed. Something terrible was happening, and I think Joan was saying, ‘Everybody sit down. Let’s not get arrested. Just sit down.’ And I’m standing there looking at this saying, ‘Why? We’re here to make our voices heard. Why should we sit down?’ I just thought this was just terrible…. I said, ‘Let’s go to the barricades! Let’s go fight the police! Let’s cross the street!’ And I was sort of surprised that people responded to that…. So there were more and more people at the barricade, and the police would not give an inch. They were, like, three deep in police, pushing the barricade. But also, there was this huge gathering crowd pushing toward the police, pushing against the police. And I was up there by the barricade, and I was telling this cop, ‘You know, if you don’t let us through, I’m getting totally squeezed here, and I can’t breathe anymore.’ And at a certain point, I felt a certain panic, like, ‘I’m going to be a casualty here.’… And that’s when the police came on the horses. So, they come out with the horses, and the pepper spray, and everybody got pepper sprayed, and that dispelled everything.”

The protesters had stuck it out for hours, un-arresting each other and gathering at different locations around the park, but the massive demonstration was over. “The bottom line was…the people who wanted to take it in a more militant direction spent all of their energy fighting rear guard stuff to keep it the way we had wanted, and therefore did not have a coordinated plan for the actual day that was able to make it happen,” Christopher says. “So it was a failure, I think, on that tactical level. We did not shut down Wall Street. We did not do the thing that we had said we were going to do. It was a huge demonstration, it was probably the largest demonstration of predominantly Black and Latino youth in the history of the city since at least the 1960s. It was a very substantial accomplishment. But it had this very mixed quality.”

Its message, however, came across loud and clear, as Pataki’s proposal for budget cuts and a tuition increase was modified shortly afterward. And SEEK and College Discovery have survived. “That day validated for me beyond measure that New Yorkers were on the same page about this,” Sandra says. “It was not about us at Hunter, it was not about the CUNY Coalition. It was like, ‘We have a mandate. New Yorkers don’t want this to happen. There’s this small group of really greedy people who run everything, who are trying to cut back something that is just of the most—life and death.’ CUNY is a lifeline for working class students in New York City.”

“They raised tuition, but they didn’t raise it the full amount,” Lenina says. “Instead of $1,000 they raised it $700. Of course, the reformist groups took a lot of credit for that…. It wasn’t the idea of 20,000 young people showing up out of nowhere, really, running around Wall Street—nah, that had nothing to do with it. And at that time, I remember, they didn’t cut financial aid as much. But our vision was so much larger. We wanted to see a school where we didn’t have to pay tuition, period.”

“You’ll Just Get Arrested”

A lot of criticism emerged from that day—notably, at a permitted march that did make it to Wall Street a few weeks later. “There were people from the Democratic Party, and Al Sharpton came up on stage and was saying, ‘No justice, no peace! No justice, no peace!’ and then said, ‘Anyone who tries to confront the police, we’ll have them arrested,’” Ramiro says. “Crazy stuff like that. And at the time, they felt that the white leadership wanted this march, they wanted this rebellion, they wanted this provocation. Four years before, at a similar protest, I think the students were able to cut through the police lines and get to Wall Street, and it was a major embarrassment for the governor, or something. And they were trying to recreate that, except that the cops were very ready. So there were a lot of arrests of students, primarily students of color. And in a sense, it was like, ‘Oh, the white leaders didn’t get arrested at all.’ So I think they realized, the revolution isn’t going to happen today, and we need to build something long lasting that’s going to at least defend what we have.”

Although white leaders did get arrested, police had definitely targeted people of color on March 23rd. Orlando’s group had a unique way of dealing with that. “In our group, there was the sense that if the cops come in, they would attack the Black men in our group,” he says. “So we had some brothers with us who were just big and tall. They were like 6 feet and just tall, and just looked like NYPD targets. And so, I remember the women in our group just crowding around them, just to make sure that they were OK…. And I’d never seen that done before. And it was like this matriarchal takeover of us to protect us in that way…. And we had students who were immigrants, too. Our group at Baruch in particular, our Black students were 99% West Indian, except for me.” But despite efforts to protect each other, students were hurt and arrested. “And then that experience happened, and we had people with immigrant status that don’t feel safe going to a rally or demonstration and getting arrested anymore.”

While planning the march, Heidi had argued against fighting back with the police. It would be hard to train tens of thousands of people not to do so, but she wanted at least the other organizers to understand the risks to undocumented people, who have fewer legal rights than citizens and can be detained by police with no charges or deported. “I think that was one thing I was really adamant about, about that rally, was to try to—I just remember being really upset about people who wanted to do stuff to provoke the cops,” she says. “I told people that we shouldn’t do that, because it was very, very possible that there were lots of people in our group, in CUNY, who didn’t have their papers. Including myself. At the time, when I was going to CUNY, I didn’t have my citizenship yet, and I didn’t quite have my green card yet.” Now, many direct action organizers are more sensitive to this fact, she adds.

“That was sort of like the high point of ’95,” Orlando says. “And it was very inspiring to take over City Hall for that day, and to see people doing adventurous, liberatory things…. But at the same time, it was also an event that set us back for the next couple of years. Because one of the things that I know for Baruch, a lot of people who come to your events and rallies and demonstrations, they do so out of this fervor, and they may not necessarily think of consequences that can be bad. And as leadership, you’ve got to prepare for that and make sure people pretty much come to an event, and they leave…. And everybody goes home, and they come back and do it again the next day. But that March 23rd rally had an effect that we had to deal with for the next three to five years…. It was like, ‘Oh, if you go to this rally, you’ll just get arrested.’”

“This Was Truly Brilliant, Because It Made the Event Real”

On the other hand, Rob points out the strengths of refusing to negotiate a march route with police. “Going into it, I thought that this is kind of dangerous, because it’s not clear that the students want to do it that way. And then when I saw it, I thought this was truly brilliant, because it made the event real. Maybe this is not the best measure of it, but it was reported on the front page of the New York Times above the fold…. The next morning—March 24th—I got a call from Dennis Rivera from 1199 and Al Sharpton at the Graduate Center…. They wanted to do something with us. This happens often. When you have an event that’s galvanized people, all the other sort of lame organizations, or the organizations that are waiting for something to happen…they call you. They say, ‘You have numbers. You have dynamism. You have something. We want to ride on that wagon.’ So this was a big event. And it was a big event because it was a riot…. We decided we would do an event with Al Sharpton and Dennis Rivera…. There were barricades on either side of the street. We marched in—it wasn’t a march. It was a parade. Was it reported in the newspapers? Well, I think the Times did put it in the Metro section. I don’t even know if they put it on the front page of the Metro section. Because it was an event of no significance at all.”

Lenina Nadal identifies a legacy beyond 1995 for the protest: “The public sector was just very angry about the budget cuts that were happening in the city, and they were so extreme—what was proposed, across the board—that it allowed for these alliances between huge parts of 1199 and…a bunch of students in CUNY who were like, ‘What the hell? We can’t afford this!’ And so all of them and the unions were able to come together, because there was such a huge attack on the public sector, and it was so blatant. And so, the city kind of erupted. And I feel like [the March 23rd protest] kind of led to a lot of smaller, little things that bubbled out of that. Sort of how Occupy Wall Street was this defining moment, with Zuccotti Park. I think that was a defining moment for the city at the time.”

And on campus, energy built for ongoing work. “It really empowered—at least at City College—a lot of the activism,” David says. “Because myself, Eric, Carlos, and a lot of other people ended up becoming very involved in student government, and that was where the trajectory of organizing went…. It wasn’t just the activists, it was the African Dance Club, it was the Salsa Mambo Club. We would do associated things like “Funk the Cuts” once a month or whatever…. So the idea was not ‘OK, the next demonstration is going to be here,’ but it was just like, ‘We’re going to call this dance at City College called ‘Funk the Cuts.'”

Kamau Franklin,* a Student Power Movement organizer in 1995 along with Orlando, says of the students who organized the March 23rd protest, “It was a lot of those organizers and activists who later on helped create SLAM! or kept SLAM! going…. It definitely started what was sort of a pinnacle, in some ways, a resurgence of student organizing, radical student organizing—really sort of left-field folks with the ability to make strong demands, a capacity to do civil disobedience or direct action, and people with various ideological belief systems who were very out about it.”

“1995, as I see it now in retrospect—it was a peak moment,” Sandra says. “And it was a peak moment because the mainstream saw it as a peak moment. The budget cuts were a citywide issue. And so the media was focused on it, the politicians were focused on it, the university was dealing with it.” But movements don’t spring out of thin air, she adds. “At times when there’s an ebb in the flow, the work that continues to be done is so critical, because that’s going to be the foundation, so that when there’s something that immediately calls for action, the foundation is set by all the work that’s done in the meantime. And so there is no random coincidence that there was just this upsurge. It’s like, the material reality of what’s happening around us, and then all the organizing work, all the activist work that we stand on the shoulders of.”

*Names of people with asterisks beside them were interviewed by Amaka Okechukwu.

Enormous gratitude to everyone who shared your stories here, and to Amaka for sharing your interviews with me. Hopefully, this is just the beginning of a conversation we can have to draw out more lessons from that day for use by contemporary movements at CUNY and beyond.